Who was Ferdinand Adolph Lange?

The story of a man who left Dresden in 1845 and transformed the remote village of Glashütte into Germany’s centre for precision watchmaking

Adolph Lange’s story is about watches and people – people who made world-famous watches, and people whose skills were attributable to his brilliant teaching. Few life stories have been as thoroughly documented as Adolph Lange’s – no doubt because of the extraordinary timepieces that bear his name or that of his descendants.

The outlook for Adolph, son of the gunsmith Samuel Lange, was not bright. Shortly after he was born in Dresden on 18 February 1815, his mother left her husband, described as a “rough character”. Foster parents had to bring up the intelligent yet somewhat frail Adolph Lange. But his fortunes changed when they managed to place him as an apprentice with the renowned court clockmaker Johann Christian Friedrich Gutkaes. This proved to be a stroke of luck. The master soon came to appreciate the unusual manual dexterity and extraordinary ambition of this young man who was burning to achieve far more in life than was typical of the average Dresden watchmaker.

In addition to his apprenticeship, Adolph Lange also attended night classes in English and French at the newly instituted technical college. It was clear to him early on that only in England and France would he be able to make the progress he desired, for these were the two countries which had made the greatest advances in the science of timekeeping. London and Paris were now heirs to the great renaissance centres of clockmaking in German Europe – Nuremberg, Augsburg, Schaffhausen and Strasbourg. Both in the glittering life of the court and in the pursuit of ever more accurate timepieces for civil and military navigation, watchmaking had the sustainable support of the state.

In 1837, three years after his apprenticeship in Dresden, Adolph Lange packed his belongings, including a book in which he would sketch and write all that he learned. It bore a letter of introduction from his master Gutkaes. His first stop was Paris where he was offered a job in the workshops of the highly regarded chronometer maker Josef Thaddäus Winnerl – Abraham-Louis Breguet’s star pupil. To make a long story short: the study sojourn stretched into three years as Adolph reached the grade of workmaster. In the end he had to turn down Winnerl’s plea to stay on, as England and Switzerland beckoned.

During this time he filled his meanwhile famous journey- and workbook with detailed drawings of watch mechanisms and tabular calculations for gearing ratios and wheels.

Lange’s tables used the new metric system based on the millimetre, which watchmaker Antoine LeCoultre was introducing at the same time in Le Sentier, Switzerland. Adolph Lange was no partisan of the heuristic method that characterised contemporary watchmaking – the trial and error that put consistent quality out of reach. Determined to change things, he returned to Gutkaes’ premises, wed his employer’s daughter Charlotte Amalie Antonia in 1842, and became the partner and driving force behind his father-in-law’s watchmaking business. The workshops had won fame through their precision instruments for astronomical calculations, sold to observatories in many different countries. One of them, regulator number 32, gave the official time for Switzerland for 60 years, before retiring to the Geneva Musée d’Histoire des Sciences.

In addition to his metric conversions and new quality standards, Adolph Lange brought back from England and Switzerland another crucial insight. It is mentioned in a letter he wrote in January 1844 to privy councillor von Weissenbach, a government official in Saxony, soliciting support for his Glashütte project: “I have combined the appealing form of the Swiss cylinder watch with the greater endurance and acknowledged precision of the very expensive and therefore impractical English lever movement.”

Indeed, the legendary Glashütte lever escapement was to become his trademark. And this foray also exemplifies the fundamental principle that would characterise all his future work: to improve and perfect. Adolph Lange’s journey- and workbook provides ample evidence of his quest for perfection. That same book became the symbolic cornerstone of Lange Uhren GmbH in the winter of 1990.

Apart from being a gifted watchmaker, Adolph Lange was also a religiously enlightened man with a social conscience. Struck by the poverty in the neglected region of the Ore Mountains south of Dresden, he decided to act in 1844. The story has been told many times of how he made relentless efforts, in letters, petitions and discussions, to promote his Glashütte project to build a watch manufactory. Finally he was able to strike a deal with the Saxon Ministry of the Interior in Dresden pursuant to which Lange would train 15 Glashütte youths as watchmakers for three years in return for a state loan of 6,700 thalers and another grant of 1,120 thalers for tools. The apprentices were further bound for five years, and would repay their training costs at the rate of 24 pence a week. Among the future watchmakers entering Adolph Lange’s employ were, according to the first personnel roster: “1 painter’s assistant, 12 basket weavers, 4 servant boys, 1 farmhand, 1 quarryman and 1 vineyard worker”.

Some of the peasant lads proved unsuitable after a short trial period. Others, however, stayed on to become the core of his workforce, which soon grew to 30 trainees. Adolph Lange was initially plagued by a woeful lack of qualified workers, apart from his brother-in-law, Adolf Schneider.

Prosperity in Glashütte

Although a chartered town since 1506, Glashütte had lapsed into poverty by 1845 – its days as a mining centre associated with the “glass ore” containing silver were long over. Its only connection with the outside world was a barely passable track and a weekly postal coach. When the illiterate coachman arrived, he used to empty out his bag and everyone would sort through the mail until they had found their own. Amid the duck ponds and dung heaps, Lange set up his first workshop, instructed his pupils, started production, built improved machines for precision parts machining, handled the correspondence and kept the books. His daughter Emma spoke of his occasional collapses from exhaustion, as he regularly worked late into the night. He invested his entire fortune, that of his wife and even the prize money for his watchmaking achievements in the struggling business.

Soon, however, his farsighted ideas began to take shape: In the wake of his own company’s growth, a host of specialized workshops sprung up like mushrooms in

Glashütte, the town whose infrastructure Adolph Lange improved dramatically during his 18-year tenure as its mayor. They crafted jewels, screws, wheels, spring barrels, balances, hands and many other parts. His manufactory outsourced the services of casemakers, gilders and engravers as well as those of three other manufactories, some founded by people whom he had trained. Hundreds of steady and well-paid jobs soon turned poverty into modest prosperity. Lange’s own business, which seldom exceeded 100 employees, formed the nucleus of German precision watchmaking in and around Glashütte. With the establishment of the German Watchmaking School by Lange’s eloquent and academically minded friend Moritz Grossmann in 1878, Glashütte finally came of age and was able to cut the umbilical cord to France and Switzerland to become Germany’s hub of horology, offering both practical and theoretical training for aspiring watchmakers.

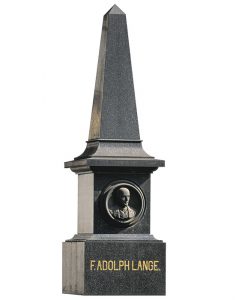

When Adolph Lange died suddenly at the age of 60 on 3 December 1875, he not only left a flourishing business and a prestigious list of international awards to his

descendants, but also a sound economic future to Glashütte. The town erected a monument to salute his achievements. Adolph Lange had brought back a thoroughly

reformed precision watchmaking culture to Germany. His mathematically calculated going-train parts, a premiere in the industry, as well as design basics such as the

three-quarter plate, the proprietary Glashütte lever and compensation balance, the precision index adjusters or balance springs with special terminal curves, represent the highest standards of watchmaking. Precision timepieces by A. Lange & Söhne, among them extremely complicated ones which fetch record prices at auctions, preserve in the hearts of watch enthusiasts the ideals of a man who wrote an epic chapter in the history not only of watchmaking but also of his Saxon homeland. Now, the new watches from Glashütte signed “A. Lange & Söhne” carry the founder’s visions into the future.

Find out more by visiting www.lange-soehne.com