William Gibson on Watches

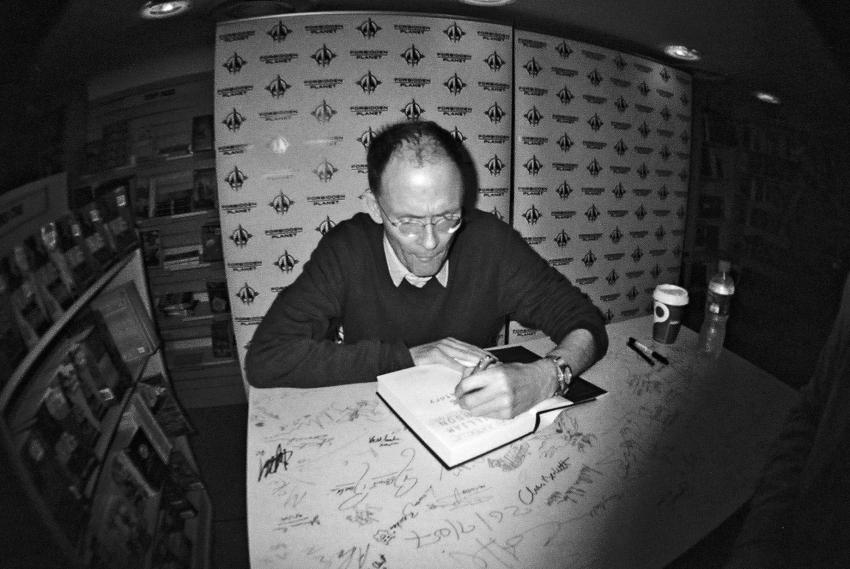

William Gibson signing a copy of his novel Zero History at Forbidden Planet in London on October 20, 2010. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

William Gibson is famously credited with predicting the internet. Early works like Neuromancer, Count Zero, and Mona Lisa Overdrive established him as a major voice in science fiction and the worlds he created still serve as a template for how popular culture views the future. If you’ve seen The Matrix or read any cyberpunk, you’ve seen William Gibson’s influence at work. Equally important, but perhaps less famous are his essays, collected recently in Distrust That Particular Flavour. Highly perceptive and suggestive, they span a range of topics from Singapore’s totalitarianism and Tokyo’s futurism, to the Web and technology’s effect on us all. The volume also contains his glosses on those essays, which were written over a span of 30 years. Brief afterwords, they are his reflections on the content, and on the person who wrote that content at a point and time, and what’s happened since. In his 1997 essay, “My Obsession”, William Gibson chronicled his interest in watches for Wired magazine. The essay is as much about the advent of the internet and sites like eBay as it is about watches, and his afterword to the essay reflects:

People who’ve read this piece often assume that I subsequently became a collector of watches. I didn’t, at least not in my own view. Collections of things, and their collectors, have generally tended to give me the willies. I sometimes, usually only temporarily, accumulate things in some one category, but the real pursuit is in the learning curve. The dive into esoterica. The quest for expertise. This one lasted, in its purest form, for five or six years. None of the eBay purchases documented [in the essay] proved to be “keepers.” Not even close.

Undaunted by his placing this interest squarely in the past, something he got over, I wanted to find out what had survived, physically or intellectually, of his obsession. It turns out, quite a lot. We corresponded via email and William Gibson shared his thoughts on collecting, how he got started, what “keepers” remain in his collection and why. We also talked about the Apple watch and what it means for traditional horology.

When you were collecting watches, how did your fascination with this class of objects evolve?

I hadn’t owned a mechanical watch since the advent of quartz. In 1997 I happened to see a very attractive ad, a simple photograph, for the first iteration of the Oris Big Crown Commander. Which proved to be unavailable here in Vancouver. I located one in Seattle and picked it up there when I next passed through. I knew nothing of Oris, but the design, which I’d later learn incorporated many (too many!) features of classic military and pilot watches, on a handsome (if busy!) black dial, appealed to me in its functionality. Various aspects of its design led me to discover the vintage watches it emulated: military-issue watches, particularly those the military had designed and commissioned. Such watches are interestingly disconnected from fashion, marketing, appeals to status, or even, in our ordinary sense, “design”.

I then gravitated to watches designed by the British Ministry of Defence during and after World War II, but I was also interested in civilian watches that in my opinion emulated the best of military design, for example the earlier Rolex 1016 “Explorer I”, which I still regard as the peak of Swiss stainless steel mechanical sports watch design.

In the end my two favorite MoD watches (both of which I’ve kept) are the Jaeger LeCoultre “Mk XI”, a pilot’s watch, and the Omega “’53”, a surprisingly large watch for its day, which was issued to air and ground crews but not to pilots. Both are stainless-cased, both have internal soft iron Faraday cages. My Jaeger LeCoultre, issued by the Royal Australian Air Force, was factory-rebuilt at LeSentier (and I suspect redialed, though they swore it was a replacement from NOS stock). My ”’53”, issued by the RAF, was an impulse buy, on the recommendation of a friend, at an antiques fair in Manhattan, my first MoD watch. It had been very nastily redialed by the MoD, as the majority were, to replace unsafe radium with tritium, but I was fortunate to be able to buy one of a tiny hoard of original NOS dials (sans radium!) from Omega Bienne when they rebuilt the watch.

I had no particular interest in military provenance, but rather in how these designs were so entirely about functionality, in an utterly life-and-death way. Very much form following function. And, as a result, in my opinion at least, often very beautiful.

If “old” people, as you mentioned in our recent discussion, are concerned that what they’ve collected will be unwanted, how is that anxiety being manifested? Some watch brands like Patek Philippe use durability, inheritance and legacy as their explicit identity.

I was thinking of someone with dozens of rare military watches. Even if they have children, will the children want their watches? It could be difficult finding the right museum to donate them to, in order to keep the collection intact. I think Patek’s appeal to inheritance and legacy still has some basis, though the wristwatch itself has become a piece of archaic (though still functional) jewelry. You don’t absolutely need one. You do, probably, absolutely need your smartphone, and it also tells the time. Eventually, I assume, virtually everything will also tell the time.

Is there something authentic in collecting we as humans are striving for? What does the impulse represent for you?

I actively enjoy having fewer, preferably better things. So I never deliberately accumulated watches, except as the temporary by-product of a learning curve, as I searched for my own understanding of watches, and for the ones I’d turn out to particularly like. I wanted an education, rather than a collection. But there’s always a residuum: the keepers. (And editing is as satisfying as acquiring, for me.)

Do you think there’s anything intrinsic to watches (their aesthetics, engineering etc.) that make them especially susceptible to our interest?

Mechanical timekeeping devices were among our first complex machines, and became our first ubiquitous complex machines, and the first to be miniaturized. Mechanical wristwatches were utterly commonplace for less than a century. Today, there’s no specific need for a mechanical watch, unless you’re worried about timekeeping in the wake of an Electromagnetic Pulse attack. So we have heritage devices, increasingly archaic in the singularity of their function, their lack of connectivity. But it was exactly that lack that once made them heroic: they kept telling accurate time, regardless of what was going on around them. They were accurate because they were unconnected, unitary.

How do you think the notion of collecting has changed since your preoccupation with watches played itself out? Scarcity (but not true rarity) barely exists any more.

The Internet makes it increasingly easy to assemble a big pile of any category of objects, but has also rationalized the market in every sort of rarity. There’s more stuff, and fewer random treasures. When I discovered military watches, I could see that that was already happening to them, but that there was still a window for informed acquisition. That’s mostly closed now. The world’s attic is now that much more thoroughly sorted and priced!

You mentioned in an interview with Wired in 2012 that Twitter had displaced watches as an obsession. They seem like very different preoccupations on the surface. What need does/did each fill for you?

I think I meant that I was spending as much time on Twitter as I had previously spent on eBay, looking for vintage watches. Essentially different activities. Twitter is public, social. The eBay watch quest was largely solitary, though I managed to make some extremely good friends in the process, so I’m still able to enjoy discussing watches with them. Twitter though, has both a meditative element and involves a sort of curation, so there was actually some similarity.

What are your thoughts on Apple’s introduction of a product that, in a very specific way, is attempting to occupy the place once held by wristwatches? Is the Apple watch a watch at all?

I backed Pebble’s original Kickstarter, then wore Pebble exclusively for the better part of a year. Fascinating experience. It’s not “a watch”, as I assume the Apple, which I’ve yet to try, also isn’t. The fundamental difference between a watch and a smartwatch is that a watch’s central functionality is to tell time in isolation. That’s the essential core goal of the science of horology, really. A watch can perform its functions perfectly from within a Faraday cage. A smartwatch can’t: its function is to be a node in a distributed network. That was easy to see in the first Pebble: it had all the physical gravitas of the cheapest Bic pen, but, eventually, it had amazingly varied functionality, via connectivity. The Apple looks like jewelry. It’ll aspire to heirloom status but I doubt it will ever be that. Attempts to render smartphones as power jewelry fail. The Apple watch, I imagine, will be a dead platform in a few years, no more collectible than old iPhones. Because it’s nothing, really, without access to a system, and the system constantly outgrows it, evolves beyond it.

What are some of the watches that appealed most to you when you were collecting? Did you have a “grail” watch?

I was looking for one, or a few, and I suppose I did find them, but I had to learn to recognize them, which isn’t always that immediate. Watches that can seem “the one” on opening the package need to be worn, understood. That modest Oris is the only contemporary Swiss mechanical watch I’ve bought, since 1997, and the only one that wasn’t a used watch. With a very few exceptions, contemporary luxury Swiss doesn’t appeal to me. I feel those watches have become power-jewelry exclusively, a class of archaic luxury item. Your phone tells more accurate time. I respond most to watches from the century in which they were utterly necessary. If someone offered me any free contemporary watch of my choosing, provided I’d promise never to resell it, I’d probably choose a Grand Seiko. I find their product, this century, more appealing than that of the Swiss.

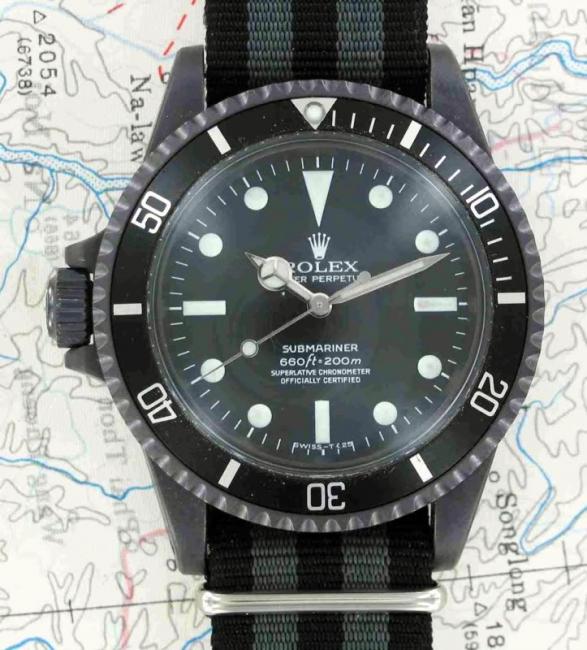

I had a lovely late-’60s Rolex 1016, but eventually let it go because there was so much overlap with the MoD watches I mentioned earlier: plain black-dialed simple single sweep. Now my only Rolex is a collaged Submariner, by my friend James Dowling. It was probably one of the first Subs to be PVD’d, though that’s long since become a thing, with Bamford etc.

James had a 5513 case and bezel standing empty, so he obtained a NOS movement and dial and hands, all 5512. Then his watchmaker moved the dial-feet so that the crown could be flipped, right to left, better for left-handed wear. Then he had the case, bezel and crown PVD’d, but prior to that he had the case and bezel lightly sandblasted. Most PVD Subs are shiny black, but this one is matte, very somber, except for the crown, which wasn’t sandblasted. None of the things about the more modern Submariners that bug me: the trim around the numerals and indices, the sapphire crystals… A grail watch had found me, right there, and I could never have imagined it!

I don’t wear it constantly, though. Some of my keepers are beaters, sturdy things that you don’t have to worry about. One is a Swiss-made Japanese quartz homage to the US military “Benrus II” dive watch, made for the fashion department store Beams. You can still find them on eBay for around $500, sometimes. Brilliant watch, licensed Benrus signage. Another is a very limited edition, built for a few friends by my friend Hyunsuk Seung, an early 1016 homage built from entirely unsigned Chinese parts, from a factory that ordinarily does faux vintage Rolex bits. Dial’s unsigned, blank, black. Basic ETA movement. Fun, a bit naughty perhaps.

I have no gold watches. Though I suspect Grand Seiko could take care of that!